»I only knew of the GDR from a children’s song

Studying in a Socialist “Fraternal Country”

Between 1951 and 1989, approximately 70,000 young people from over 125 different countries studied in the GDR, with around half of these coming from socialist countries. Around 7 percent of foreigners living in the GDR came to the country as students (this figure does not include Soviet soldiers, who are an exception). Students, trainees, and apprentices from Vietnam were educated in the GDR from 1966 onwards (Feige 1999).

Representatives of a Heroic Nation

The GDR news agency proudly reported that “over 150 young people from Vietnam, who will commence studying in GDR universities and technical colleges at the start of the academic year, arrived in Berlin on 17 August 1971. A total of 1,100 young representatives of this heroic nation have now enrolled at universities in the Republic.”

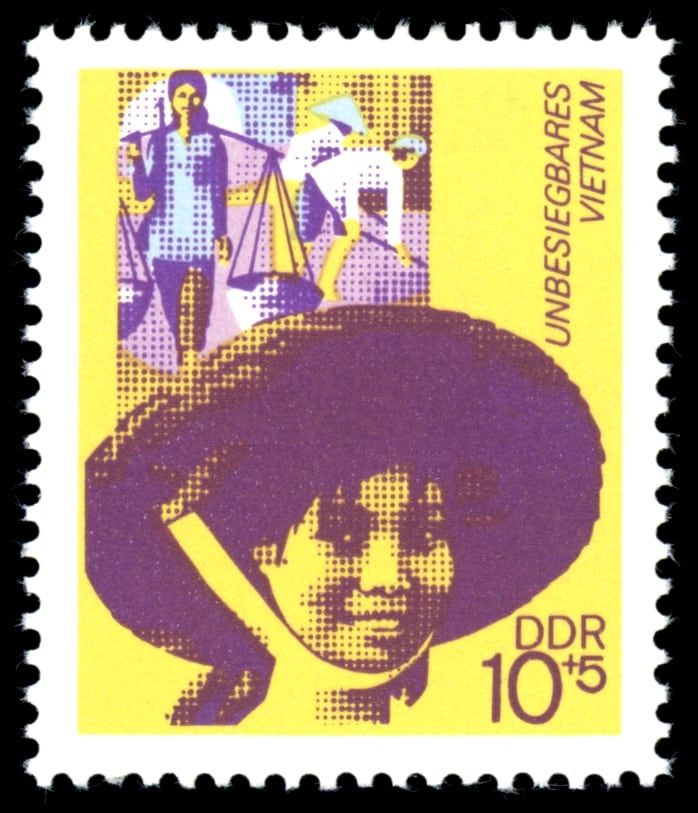

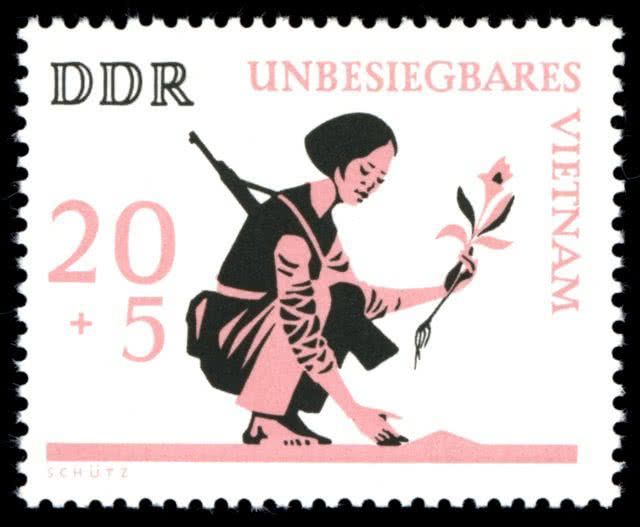

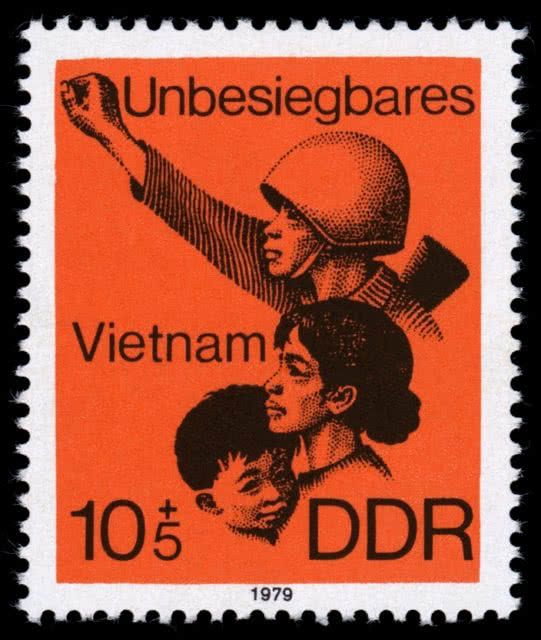

“Invincible Vietnam”

The GDR felt a particular connection with Vietnam, as both countries were outsiders in global politics. Images from Vietnam were everywhere, having been disseminated prior to the arrival of the young Vietnamese students to highlight the special relationship between the two countries. An example was the stamp collection “Invincible Vietnam”. Eight stamps with a supplementary cost that went to charity and a circulation of up to 9,000,000 copies per stamp conveyed romanticized imagery of war, post-war reconstruction, and happy people in almost every household.

»We knew that the quality of education in the GDR was good

Like Pham Thi Hoai, Alemayehu Gebissa came to the GDR to study, arriving from the socialist People’s Democratic Republic of Ethiopia to the Wilhelm-Pieck-Universität in Rostock. His country had suffered from devastating famines and was torn apart by civil war. After completing his education and achieving high grades, his college delegated him to the GDR in 1986 to study at the postgraduate level.

With residence in the GDR, Alemayehu Gebissa was able to further the education that he had received in Ethiopia. Special qualifications and better living conditions were also the hope of many of the other migrants who came to the GDR as workers.

Life as a Worker in the GDR

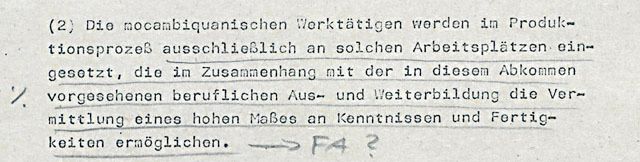

By far the largest group of migrants in the GDR were workers. Their life was governed by labour and production. From 1979 onwards, Vietnam and Mozambique sent the highest number of workers. Their living and working conditions were outlined in detail in bilateral agreements that emphasized mutual interests and cooperation, and contractually guaranteed a qualification in a technologically advanced country.

The document states: “(2) In line with the occupational education and training envisaged by this agreement, the Mozambican workers will be solely employed in the processes of production in roles that enable them to acquire a high degree of knowledge and skills.”

The agreements with Mozambique (1979) and Vietnam (1980) were of major significance to the GDR. These were designed to offset a dramatic labour shortfall in the 1980s and to maintain production levels. Intergovernmental agreements had in fact existed since the 1960s with friendly countries––initially with Poland and Hungary, and later with Algeria and Cuba. However, these countries gradually stepped back from cooperation in the 1980s, sending fewer and fewer workers to the GDR in a period when demand was increasing dramatically. The agreements regarding “temporary employment” (Contracts and Interests) with Mozambique and Vietnam were classified; the workers in question only knew the contents of their work contracts. While they each had their own motives for applying for residence in the GDR, their routes there were different.

The document states: “ Template for the Secretariat of the SED Central Committee

2. According to calculations by the GDR Ministry of Finance, the average contribution of a Mozambican worker to GDR national income in 1986 amounted to 18,483 East German marks net. The employment of a total of 13,000 Mozambican workers from 1988 onwards thus corresponds to an annual contribution of approx. 240 million East German marks to the national income.

3. The employment of additional workers from Mozambique is a means of partially compensating for the decrease in or cessation of the employment of Polish and Cuban workers.”

Solidarity with Moçambique

Since the 1960s, the GDR had supported the Mozambican freedom movement FRELIMO (Frente da Libertação de Moçambique) in its struggle against Portuguese colonial rule. Not until the collapse of the Salazar dictatorship in Portugal and an 11-year war that left around 30,000 dead did Mozambique become independent in 1975. FRELIMO took power and most Portuguese citizens left the country, leaving behind massive economic problems and a glaring skills shortage. In order to quickly rebuild the economy in an independent Mozambique and to combat illiteracy, FRELIMO pressured successful students into vocational training or put them to work as teachers. Orquídea Chongo had her schooling cut short in this way, but with her family’s support, she sought alternative ways to advance her education.

»I thought that this way, I might have a better life

From a “Young Nation State”

After the end of colonial rule there, Mozambique was among the countries that the GDR designated as a “young nation state” and was also targeted by it (Wolf 2000, p.152). In addition to ideological proximity, support for anti-colonial rule in Africa and Asia fulfilled one of the GDR’s concrete political objectives: its recognition by the governments of these newly founded states. The GDR also combined key economic interests with cooperation measures. Mozambique’s independence coincided with a drastic shortage of foreign currency and impending insolvency in the GDR. Mozambique was viewed as one of the “selected and allied African states” with which the GDR was engaged via foreign policy efforts, immediate action programmes, and an export offensive. The goal of the cooperation was to generate foreign trade surpluses and foreign currency (Döring 1999).

The concept of international solidarity formed the ideological basis of migration to the GDR. But beyond this notion lay concrete political and economic interests.

»Cash bribery made it possible for me to go to the GDR

Particularly in countries that were at a difficult stage of reconstruction after long and devastating struggles against colonial rule, the prospect of leaving was often deeply imbued with the hopes and investments of the entire family. To protect her son from conscription, Nguyen Do Thinh’s mother left no stone unturned.

Für Frieden und Völkerfreundschaft!“For peace and friendship among the peoples” Greeting used by the Young Pioneers in the GDR

Political Emigrants––a Form of Asylum

The GDR opened its doors for another group of people: political emigrants. These were the only ones for whom a leaving date was not set when they entered the country. Political refugees could receive asylum in the GDR. Since 1968, a discretionary provision of the constitution allowed for the taking in of people persecuted for political reasons. They could take refuge in the GDR if they were considered politically “desirable” (Poutrus 2003). Taking in threatened or persecuted members of communist “allied parties” from other countries was considered an act of proletarian internationalism.

»I only found out at the airport that we were going to the GDR

The life of Kadriye Karcı, a student in Turkey, was in danger following a 1980 military coup and a subsequent wave of arrests. For her own safety, she was brought to the GDR in 1985 in secret.

Venceremos!

With around 2,000 people, Chilean refugees formed the largest group of political emigrants that took refuge in the GDR. They were offered comprehensive state support, including preferential access to newly built apartments, interest-free loans, as well as a bridging allowance upon arrival (Koch 2016). Carlos Medina and his wife were members of the Communist Party of Chile. When a military coup in 1973 resulted in a hunt for opposition party members, Medina and his wife fled to the GDR.

»We wanted to see for ourselves what an existing socialist state looked like

Carlos Medina was also able to perform on stage in the GDR and received an excellent education in theatre. The sympathy in the GDR for Chilean politics under Allende’s government, as well as the outrage at its bloody overthrow, was beneficial to him. For many GDR citizens, these were genuine reasons for solidarity with Chilean emigrants. The government attempted to steer this sentiment in a specific direction at a number of state-organized solidarity events.

Solidarity as Duty

The principle of mutual support in the Socialist bloc, beyond national borders and in particular for repressed and militant groups, was shared by many. However, the privileges granted to Chilean emigrants led to mixed feelings for some. The GDR Solidarity Committee appropriated feelings of solidarity through large-scale events, posters, stamp collections and above all with collective funding drives––with consequences should the latter be evaded. The duty of solidarity also created some resentment.